Yesterday, I came across a very interesting video presenting a debate between a scientist and a flat-earther (i.e., someone who believes the Earth is flat). These two guys were in their respective cliché to their higher extent: on the one hand, a 50-year-old bearded scientist, wearing a faded unpaired suit that her wife imposed on him in order to be presentable on TV; on the other hand, a hyperactive young man wearing sneakers, a cap and a Nike t-shirt. The clash would have seemed unavoidable. However, these two challengers turned out to have more in common than expected at first glance. More precisely, they both share the same principles for guiding their search for truth, but deduce different conclusions from these.

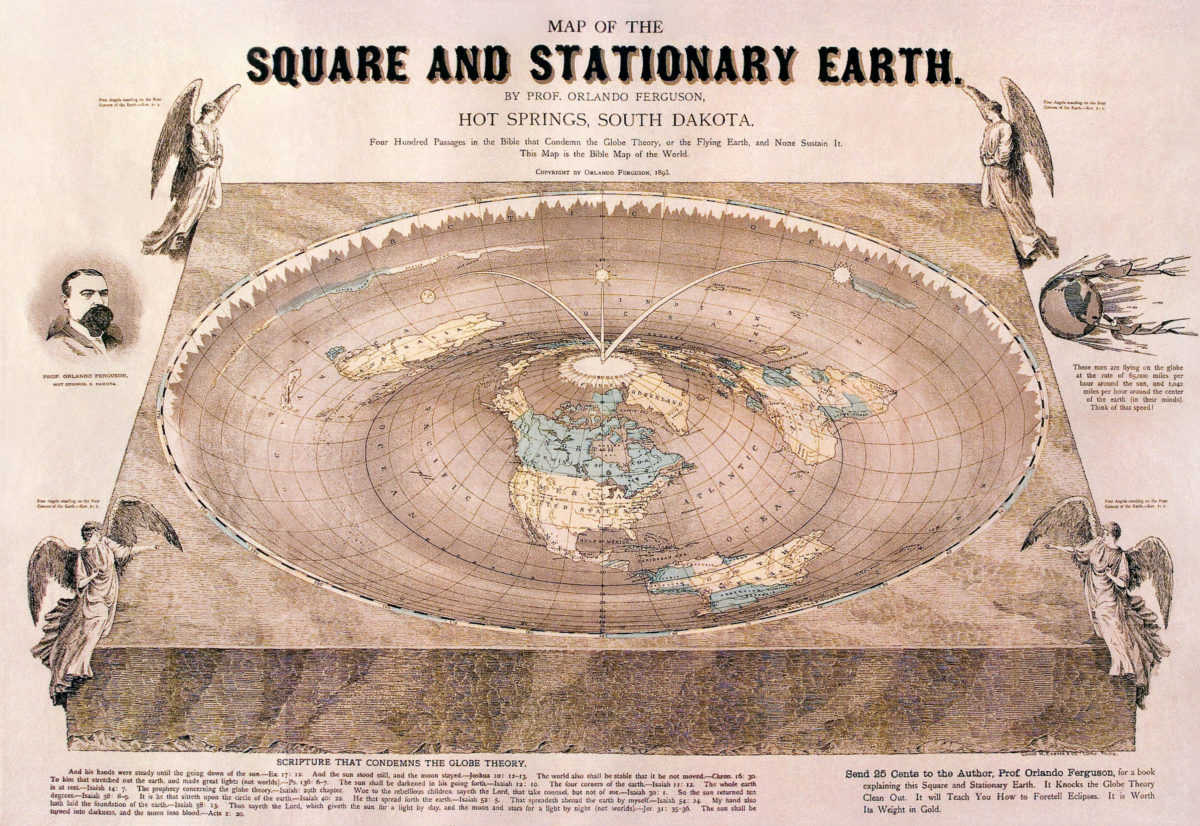

An interesting moment in the debate occurs when the scientist explains to his opponent one of the very fundamental principles ruling science: Ockham’s Razor. According to this principle, if two theories demonstrate the same explanatory power for a given set of facts, the scientist tends to choose the one with fewer assumptions, the most economical and the most reasonable. The flat-earther wisely asks: what is the most reasonable between, on the one hand, a stationary and flat earth, and, on the other hand, a moving and spherical sphere? For sure, a stationary and flat earth requires the least amount of assumption: we daily experience no curvature at all when looking at the horizon from a tower, and we don’t feel seasick due to the rotation of the Earth. Ockham’s Razor seems to give advantage to a flat Earth theory. Flat-earther won this round.

However, the scientist would argue that we don’t have to trust our senses every time: we feel no motion because the motion of the Earth along its axis is not strong enough to be perceived by the human body (but very sensitive experiments can detect it). So “perceptions are sometimes misleading in the scientific inquiry”, would conclude the scientist. With the same kind of argument, the flat-earther can reply that the perceived curvature of the Earth we experience in a plane by staring at the horizon is simply explained by the curvature of the cockpit’s glass. Thus, he agrees with the scientist’s claim that our senses are foolish. But this scepticism about perceptions leads to opposite conclusions. In the same vein, it is pretty outlandish that NASA sent humans in a box of metal 380 000 kms away from Earth. The passengers experienced extreme temperatures, landed on an unknown piece of rock, walked freely on it and came back to Earth safely in the same box of metal, even if, only 60 years before, the first planes were unable to fly more than a few meters without crashing deadly on the ground. For sure, the hypothesis of an astronaut filmed in a swimming pool of a Hollywood studio is more plausible and requires fewer assumptions. Furthermore, during the Cold War epoch, so much was at stake for the US that it was very tempting for them to simulate a successful landing in a cinema studio instead of taking the risk of a possible unexpected rocket explosion in the air. The flat-earther seems to have won this round again.

For the scientist, this advocacy could seem stupid: of course NASA’s outstanding achievement can be explained by the tremendous amount of money spent on R&D during the Cold War, and the round shape of the Earth has been confirmed by a lot of experiments… However, the problem is still there: the scientist and the flat-earther use exactly the same epistemic principle for seeking the truth: Ockham’s Razor. They both demonstrate a strong commitment to following this principle, but deduce deeply different conclusions from it. This point is even more obvious when they both pretend to adopt scientific scepticism: observing the world, stating a theory, making predictions, ruling out this theory if the predictions contradict observations, trying to find a more adequate theory, etc. I do think that both of them are sincere and apply this rule correctly. The very difference rest in the fact that the classical scientists have been applying this principle for many centuries, and statements that appear to follow this principle from the point of view of the flat-earther have been ruled out for ages by the scientists. Perhaps the flat-earther missed the train, and the scientist’s one is twenty centuries ahead. I am not here pretending that the flat-earther lives in the Middle Ages and believes in fairies and dragons. I just state that he is indeed a scientist – he adopts the Ockham razor principle, and he is not dogmatic, thanks to his skeptical posture – but he does not take into account the 2000 years of scientific heritage. He does everything by himself, relying on the application of fundamental scientific principles to his daily life.

Our flat-earther is like a DIY scientist, a self-made scientist, a liberalised scientist, a uberized scientist. Flat-earther is the enfant terrible of the scientific method, the illegitimate son of rational autonomy of thought, the best student of Mr Ockham’s class, the mandarin of the fundamental scientific principles. This nomad scientist assaults the scientists’ strongest building in their inner foundations, forcing these scientists to argue both for and against their fundamental principles. And it is a good thing for two reasons. First, he insatiably wakes up the old queen Science from her lazy dominant position, from where she thinks that so obvious things such as planetary motion and evolution theory are carved in stone forever. Then, Science is forced to urge her servants to renovate her kingdom’s foundation at every assault of the heretics. Second, the debate we depicted points out that science doesn’t rely on static and eternal epistemic principles but merely on temporal procedures inspired by these principles. Such procedures highly depend on the grounding historical context and modify their shape according to the state-of-art of that moment. These epistemic strategies are like chameleons fed by an inherited historical background of facts and theories. What is scientifically true is not a matter of rational reasoning but a matter of arrangement of previously collected data in such a way that it produces a coherent theory. Science has always argued a method, but how many books did she wrote about? Has anyone found a book titled “The art of doing science” or “Key principles to be a good scientist” in a library? The reason is, surprisingly enough, that science doesn’t have any systematic method per se. However, this lack of systematic methodology is not an Achilles heel but guarantees the robustness of the scientific inquiry. Good science can adapt its strategy in real time to solve more efficiently the problems it faces. This plastic method is indebted of ages of past scientific investigations. In contrast, the flat-earthers’ method starts from scratch again and again.

This paper draws the conclusion that the classical scientific inquiry cannot be characterized only by its use of a certain static set of epistemic principles (for instance, Ockham’s Razor), otherwise she should definitely agree with the flat earth theory. Instead, scientific inquiry uses a weaker version of these principles, fed by a background of past events, theories, and observations which has been conducted ages ago. There is no such thing as an absolute scientific method. There is no method but a plastic one, always in movement and redefinition.